Landscape Artist of the Year

A Personal Reflection

I wanted to share a little about my experience on Landscape Artist of the Year.

As many of you will know, being an artist is not easy. To give a bit of context, I received a message on Instagram asking if I would like to submit a work for the show. I remember thinking to myself, “What do I have to lose?”

I had painted outdoors often in the past — at one point, almost every day — but that was primarily in watercolour on watercolour paper. At the time of receiving this message, however, I had stopped painting outdoors, believing ink marbling to be my chosen path. I decided to take a punt with the ink marbling and submitted my painting Ethqara.

They wrote back fairly quickly, saying they loved it and would be happy to accept me on the show.

This left me in a bit of a pickle. I had to decide whether to continue in the direction of my submission (ink marbling) or return to painting outdoors in watercolour, which I had plenty of experience with. At that moment, though, I didn’t feel confident in my watercolour practice, so I decided to try my luck with ink marbling en plein air.

I had no idea what was going to happen or how it was going to turn out.

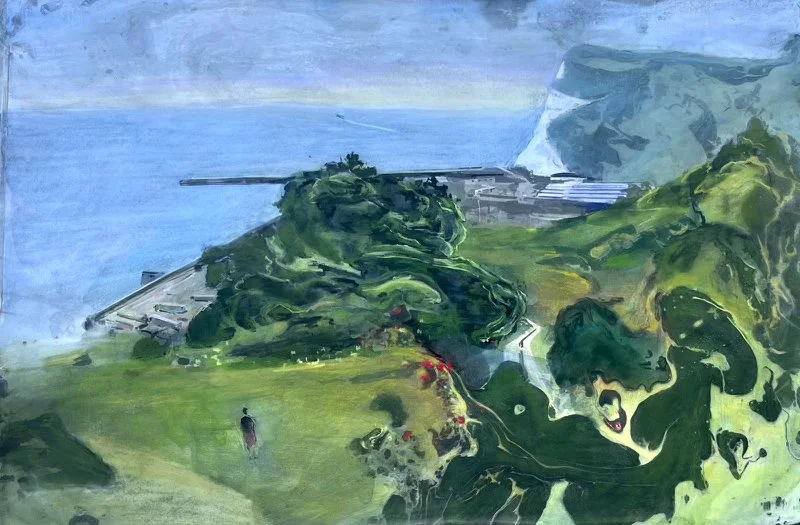

My submission, Ethqara, at the Port of Dover.

The Day at Dover

On the day, I felt quite blissful. I usually start my mornings with a meditation, and I had a particularly good experience that morning. For some reason, I just felt that things would work out.

We were placed on the White Cliffs of Dover, and before taking us to our pods, they brought us further down for some interviews. I caught a glimpse of the cliffs from where we were standing and immediately knew this was the view I wanted to paint. It had a beautiful diagonal composition, with a path leading the viewer’s eye through the scene and plenty of natural shapes that I felt would work well with the marbling.

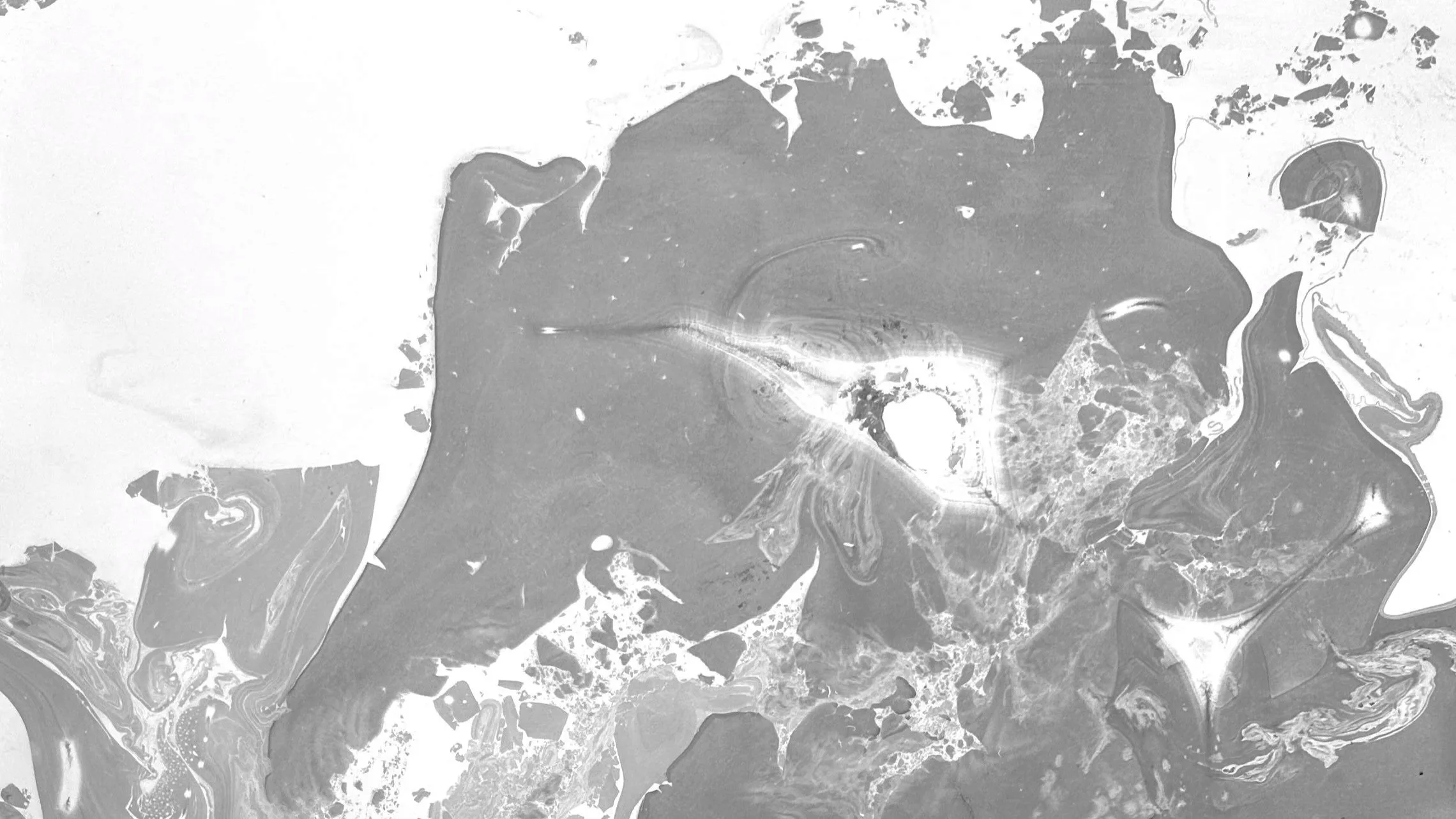

I began with a sketch, reversing the image because I knew that once I laid the paper onto the marbling bath, I would get a reversed image. Once the sketch was complete, I knew what I needed to do with the marbling: concentrate the patterns towards the bottom left and leave the top right area more open.

Then came the biggest challenge of the day — navigating the windy conditions on the cliffs with such a delicate process. I had four sheets of paper to work with.

I said my silent prayers and began the first attempt, which went everywhere because of the wind. Try number two was no better, and try number three failed miserably.

Holding my final sheet of paper, I thought to myself: forget the prayers — just be quick, place the ink where you want it, and catch it without hesitation. And voilà — I managed to get something I could work with. From that point on, I felt a huge sense of relief. The hardest part was over, and I had given myself the best possible chance.

The view I managed to photograph

I had no real interest in the ferry port, all I wanted was a view of the white cliffs which would say much more about the place than any boats or ports could!

A quick composition sketch

You can see me thinking in terms of blobs of ink, dark shapes in the bottom right corner which when caught with paper we’d see the reverse of.

Finding Confidence

As the day went on, I felt a calm confidence growing. I knew I was giving the painting my best shot and that my state of mind was good. Looking at some of the other contestants’ work, I was quite impressed and knew I had to step up if I was going to go through.

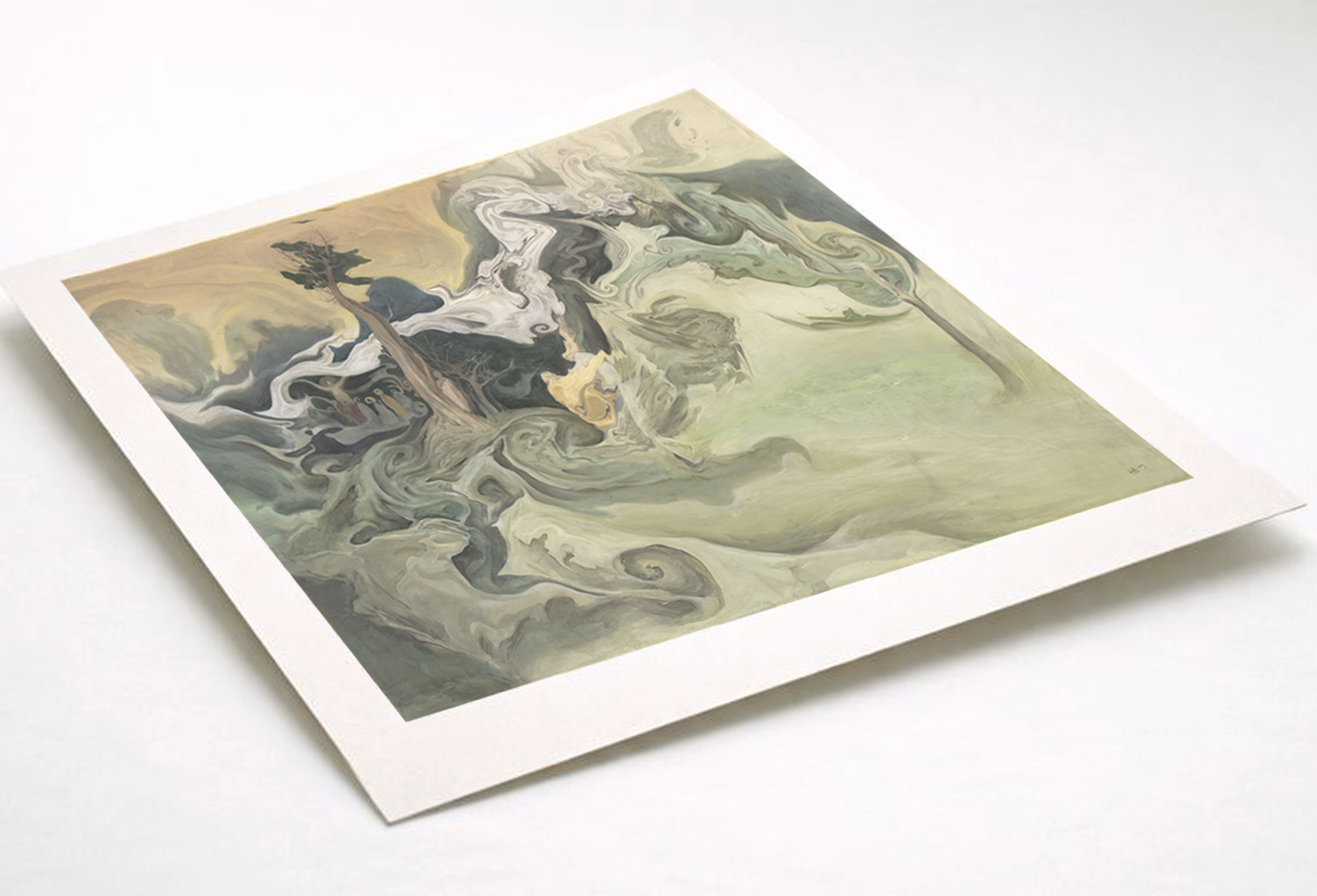

I worked with more intensity, blocking in washes of watercolour and then refining the piece with pastels. Towards the end, I began to look more closely at the reference, noticing bold, saturated reds, yellows, and greens, which I worked into the painting with the pastels.

I was particularly proud of the white cliffs, where I felt I had managed to capture the atmosphere I could see on the day. The tree shape in the centre became quite opaque as I continued to naturalise the ink-marbling forms, trying to bring them closer to the tree I was observing. In hindsight, I definitely overworked it — but it’s always easy to say what you could or should have done after the fact.

Final Heat painting

Reflections

I really enjoyed the day and meeting my fellow contestants. When I was selected to go through, I felt thrilled and quietly emotional. Years of working away and trying to improve seemed to have accumulated in that moment, and I felt deeply grateful.

At the same time, I felt a slight sadness for the other artists, who had all worked incredibly hard to get to that point. Art is completely subjective, and everyone there had earned their place.

I wanted to share this experience to offer a more personal perspective on what aired on television.

The next episode — the semi-finals — airs on 22 February, and I’ll keep you posted.

Till then thanks for your support!

Why Mountains?

Prasad in Italy, 2021

I grew up in the foothills of the Himalayas, though the meaning of that place only became clear to me after I left. We meditated morning and evening, and the rest of life was ordinary childhood — playing football, climbing trees, laughing, getting into trouble, fighting, making up. Through all of it, the mountains were simply there: steady, familiar, almost like a quiet witness in the background.

When I moved back to the UK at sixteen, I felt a kind of isolation, the sense that I didn’t quite understand the culture I’d returned to, or how I was meant to fit into it. That feeling pushed me inward. It made me reflect on myself, and who I was in all of this.

Over time, I realised that the silence I rediscovered in myself was the same silence I’d felt in the presence of the mountains. That awareness has stayed with me, and it’s why mountains continue to appear in my paintings — not just as landscapes, but as reminders of that inner stillness.

Why Mountains Carry Meaning Across Cultures

Sunset over Blue Mountain

I never thought of mountains as symbolic when I was young. They were just part of the environment. But the more I painted them, the more I noticed how often mountains appear in different traditions as something that points inward.

Certain themes repeat themselves:

steadiness

perspective

quiet

clarity

elevation

the sense of something unchanged

A mountain rises, but it doesn’t move. It provides scale. It places things in context. It quietly suggests a way of seeing that isn’t caught up in the immediate.

Mountains in Classical Chinese Landscape Thought

Sesshu Toyo (left) & Huang Gongwang (right)

In classical Chinese culture, mountains were associated with perspective and reflection. Scholar-officials often kept landscape scrolls nearby. When work became mentally heavy, they would pause and look at a painting — not to escape life, but simply to take a step back and reset their minds.

A mountain painting served as a reminder of something steady and larger than whatever problem was in front of them. The practice was a way of orienting the mind.

Chinese landscape painters weren’t trying to record a place exactly as it looked. They were expressing the inner experience of being with mountains — the space, the quiet, the sense of proportion.

Mist and empty areas in paintings weren’t just atmospheric; they created openings for the viewer’s mind. The unpainted space mattered as much as the painted forms.

This is why mountains became central subjects. They offered a natural shape for ideas about steadiness, balance, and the relationship between form and emptiness.

Huang Gongwang & Sesshū — Two Approaches to Clarity

Two painters from different traditions illustrate two useful ways of understanding insight.

Huang Gongwang (China)

Huang worked slowly and patiently. His landscapes developed through observation, adjustment, and layers of wash. His approach suggested that understanding is something gradually cultivated.

Sesshū Toyo (Japan)

Sesshū sometimes worked with sudden, spontaneous strokes, especially in his “broken ink” pieces. These paintings feel immediate, as if the form appeared in a moment of clear perception.

These two approaches — gradual and sudden — appear in many traditions. They’re not contradictory; they describe different aspects of how clarity can arise.

My Process: Spontaneity First, Then Structure

Chinese Ink on Canson Arches paper

My own way of painting mountains reflects both of these approaches.

Before anything else, I begin with a spontaneous marbled ground — ink and water interacting in ways I can’t fully control. Shapes emerge on their own. This part always feels fresh, almost like the first hint of an idea revealing itself.

After that, I work in transparent washes, gradually building the forms. This part is slow, steady, and considered. The painting takes shape through repetition and adjustment.

That combination — a spontaneous beginning followed by patient refinement — feels close to how understanding often forms in life. Something appears, and then you spend time working with it.

Nanao Sakaki — A Useful Image

There’s a poem by Nanao Sakaki that expresses something simple but accurate about mountains and the self:

Look! a mountain there.

I don't climb mountain.

Mountain climbs me.

Mountain is myself.

I climb on myself.

There is no mountain

nor myself.

Something

moves up and down

in the air.

It suggests that the boundary between the mountain outside and the mountain within isn’t always clear-cut. It’s an idea that aligns with how many Asian traditions think about nature and the mind.

A Mountain for Your Wall, A Mountain for Your Mind

Crimson Sunset Peaks

To own a mountain is not to own a view.

It is to keep a reminder of something you already know:

that stillness is available

that perspective is possible

that the mind can rise above its noise

and that something steady exists beneath change

A mountain on the wall becomes a quiet presence —

not demanding attention, but offering it back to you.

A companion in clarity.

A steadying force.

A presence that watches without moving.

This is the quality I look for when painting mountains — not dramatic scenery, but a sense of the witness behind it.

Available prints